Rupert's

Comeuppance

The

unraveling of a cozy relationship

By Adam Davies

[Webmaster's

note: At first sight, a lengthy article about a British tabloid's rise

and eventual fall would seem a very strange fit for this website. But

what this piece shows is how a publication was willing to sell its

scruples for power and influence and then used that power and influence

to stampede its readership into various quixotic crusades in order to

maintain and increase its power and influence in what looked to be a

never ending circle – until its hubris brought it crashing down like

Icarus. Such a careful dissection of this process can aid us greatly in

understanding the incestuous relationship between our own press and

government and how the two use us as a handy tool to leverage ever more

power to themselves. We'll never effectively fight the harm this tight

embrace causes until we learn to see it. So study this piece carefully

and learn from it.]

The downfall of British Sunday paper the News of the World is a story

with particular resonance for boy-lovers as that paper made itself into

one of our chief tormentors over many years. Perhaps it will yet bring

down the empire of its proprietor, Rupert Murdoch (also proprietor of

large chunks of press and TV in the US, China and many other

countries). But for decades, the combination of Murdoch and the News of

the World seemed like a marriage made in some particularly cheesy

version of heaven.

Founded in 1843, from the start the News of the World pioneered a new

form of yellow journalism, based mainly on reports from the

(small-time) police courts, with a heavy emphasis on the more salacious

cases to be found there. Others soon followed, and by the 1880s much of

the press had been dragged down to the News of the World's level, and

the paper no longer stood out. It was the North London Press that broke

the Cleveland Street Scandal

1,

the Illustrated Police News that led the sensationalism around Oscar

Wilde's trial and the (supposedly upmarket) Pall Mall Gazette that in

1885 published the Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon.

WT Stead

and Eliza Armstrong and headlines from The Maiden Tribute of Modern

Babylon

Readers will recall that the Maiden Tribute was an epoch-making story

in which the editor, W.T. Stead, bought a little girl and had her

vendors prepare her to be sent to "the Continent" as a white slave.

Although there was a large amount of reportage surrounding it, clearly

the central star of the central story was Stead himself. It was a great

innovation and discovery, that newspapers could so directly and openly

manufacture the news that they would then report. The professional

propriety of it was questionable from the start, especially the extent

to which Stead's enquiries themselves may have generated the offer that

he accepted.

The Maiden Tribute was politically very influential. It helped

establish a new victim culture, and was deliberately timed to create a

panic that would help force through the Criminal Law Amendment Act

1885, and which codified that new victim culture into law. As well as

raising the age of consent to 16, this Act criminalised 'gross

indecency between males', meaning all gay sex (not just anal sex

('buggery'), which had always been illegal). The thinking behind this

was very much like today's thinking about boys. No man in his right

mind, it was felt, would consent to having any 'gross indecency'

performed on him, and so any apparent consent was immaterial, probably

the result of corruption due to having been the victim on previous

occasions. And, as with modern boy-love, it was believed that by far

the predominant form of homosexuality would be a higher ranking or

stronger man imposing himself on a weaker, or else in some way paying

for sexual favors. (This almost certainly led, four years later, to the

next tabloid sensation – the Cleveland Street Scandal.) For instance,

the Oscar Wilde case involved both differences of social rank and gifts

that could be regarded as payments. It is worth remembering that this

was all the work of liberals and helped define what was called the

'progressive era'.

New ownership in 1891 gave the News of the World a shake-up and a new

lease on life. Partly this was by improving distribution, making the

paper more easily and universally available than its competitors. But

this went hand-in-hand with a thorough absorption of the lessons of the

Maiden Tribute, especially the idea of making the paper and its own

reporters the stars, and Stead's other implicit lesson: sex sells. From

now on the News of the World would bring its public a cheap, ersatz

Maiden Tribute, not every week, but often, and as its signature story

type. The stereotype story in its golden era: send an 'undercover'

reporter to some small local massage parlour, where he would aim to

gain a masseuse's trust and negotiate some 'extras'. The reporters were

supposed to excuse themselves before enjoying the extras, but who knows

if they did. The paper would then report the massage parlour -- 'hand

over its dossier' -- to the police and photograph the arrests, but the

story would be mainly about its reporter's daring deeds, titillatingly

not-quite-describing the naughtier bits. Surely this is the true

meaning of sleaze! A further advantage was that, since such stories had

zero topicality or news value, it could run them whenever it liked.

Its sleazy reputation was soon established. George Riddell, its

business manager in the 1890s, belonged to the same London club as

Frederick Greenwood, who had succeeded Stead as editor of the Pall Mall

Gazette. Greenwood affected not to have heard of the News of the World,

so Riddell sent him a copy. Next time they met, Riddell asked what

Greenwood had thought of it. "I looked at it," replied Greenwood, "and

then I put it in the waste-paper basket. And then I thought, 'If I

leave it there the cook may read it' -- so I burned it!"

Despite

such discerning reactions from the upper class, the paper became ever

more popular with the British working class, unfortunately having a

large influence on its character. New titles tried to imitate it,

several of them still leading papers today, including the Mail, the

Express and the Mirror, but somehow none of them quite dared to plumb

the same depths. Perhaps this was partly because these parvenus

published daily, whereas the News of the World was always happy to

remain Sunday-only: for the British working class, Sunday was the day

of sanctimonious sleaze.

By the early 1950s, the News of the World was the largest circulation

paper the English-speaking world has ever known, with a regular

circulation a little under nine million and breaking through the nine

million barrier on especially sensational weeks. This was the time of a

major state crackdown on homosexuality, during which Alan Turing was

driven to suicide and Quentin Crisp prosecuted. The paper's exposure of

various homosexual 'vice rings', such as Lord Montagu of Beaulieu,

Peter Wildeblood and friends (and the scout troupe that camped on

Montagu's land) with headlines like 'The Most Evil Men in Britain'

helped it past the nine million mark more than once.

By 1968, newspaper circulations generally had shrunk, but the News of

the World remained Britain's best-selling paper by some margin when the

Carr family, owners since 1891, sold it to Rupert Murdoch, then owner

of a modest but thriving group of Australian newspapers, in preference

to wannabe press baron Robert Maxwell's attempted hostile takeover.

Shortly afterwards, Murdoch also took over an ailing daily newspaper,

the Sun, which he transformed, in his own instructions to his first

editor, into "a hard-hitting paper with lots of tits", taking the

British daily press to a new level of vulgarity and crassness, or

rather making a success of that transition in a way that the Mirror,

Mail and Express had never quite managed, and even now didn't quite

have the brass neck to emulate fully, vulgarity and crassness that

perfectly complemented the News of the World, which he was happy to

leave just as it was. The Sun rapidly became Britain's biggest selling

daily, concentrating on reducing politics to soundbite slogans for

idiots surrounded by pictures of young women with their breasts hanging

out, while the News of the World remained its sleazy old self. It was a

winning combination and the foundation of the greatest global media

empire the world has yet seen.

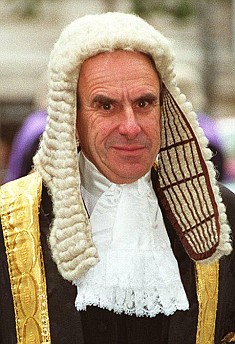

Rupert

Murdoch is the son of Australian press magnate Sir Keith Murdoch, who

first made his name by making bold, sensational claims about the

Gallipoli campaign in World War 1. The fact that these claims ranged

from wild exaggerations to outright fabrications did nothing to blunt

their impact, and much to set the tone of what was to come. They

transformed a young unknown into one of the leading journalists of his

day, and also earned him a role in creating Britain's intelligence

agencies (with which the Murdoch family may have continued to have a

cosy relationship). Keith Murdoch learned the lesson, practiced it

throughout his successful career as an editor and then proprietor in

Australia, and passed it on to his son: big, bold, memorable stories

bring success; truth is a pettifogging detail.

On Keith Murdoch's death in 1952, some of his papers had to be sold

off, but enough remained to give Rupert a good start. He never edited

the papers himself, but took an active interest and somehow brought out

in his editors a unique and highly characteristic level of high-pitched

vulgarity. It was salable from the start and his Australian group of

papers flourished and grew, extending to New Zealand in 1964. But his

entry into the British market in 1968 was a transforming breakthrough,

both for him and us, marrying his sensationalism with the News of the

World's sleaze.

By the 1970s it was becoming harder to persecute gays, but a new target

arose. Dr Frits Bernard had been quietly developing the idea of

self-help and emancipation groups for self-identified pedophiles (both

boy- and girl-lovers) in the Netherlands since the mid-1950s, but in

the early 1970s he gained the support of the NVSH (Dutch Society for

Sexual Reform), at that time a mass-membership organisation, as it was

the only source for birth control products, and organised a series of

international conferences at Breda. From these the idea of organising

as pedophiles spread to young BL and GL idealists across Europe, and in

Britain led to the founding in 1974 of PAL (Paedophile Action for

Liberation) and PIE (Paedophile Information Exchange). It was not the

News of the World, but a smaller imitator, the Sunday People, that

first spotted the opportunity, infiltrating PAL by sending an

undercover reporter along to its meetings, which were open to all

comers, and befriending the leading members, and then reporting on who

they were and (with some dramatic license) what they said. The

conversations were mildly salacious, but for the paper and its readers,

their sensibilities cultivated by generations of

News-of-the-World-style journalism, the main story was that PAL

existed, and the main point of interest was who its members were,

leading to victimisation by neighbours, landlords, employers etc.. The

exposé led to PAL's rapid disintegration.

Murdoch's News of the World was late to the table, but made up for that

with its greed once it got there. Sunday People vs. PAL was a spat

between lightweights compared to News of the World vs. PIE. The paper

ran a relentless campaign of intimidation against individual members

and attendees at PIE events from 1977 to 1983, with non-story after

non-story where people were named as PIE members, often with quotes

attributed to them that were boldly fabricated in the style pioneered

by Keith Murdoch, designed to fit the paper's 'angle' and drench

everything it touched in its own characteristic sleaze. When there was

some actual event to report, such as a PIE spokesperson being barred

from a conference, or if it was a slow time for news, the rest of the

tabloid press would tag along. The strange, hand-in-glove, implicitly

corrupt relationship between the press, especially the News of the

World, and the police and courts, led to two trials of leading PIE

members, in 1980 and 1984, and the jailing of four of them for

political offences. It was with the second of these that PIE gave up

and closed itself down, depriving the News of the World of a regular,

staple source of content.

The relationship

between the British press and courts was (and remains) that most judges

share the press's sleazy worldview. It is a curiously one-sided

relationship in that the judges seem to crave tabloid approval and are

known, in sentencing speeches, to thank particular tabloids for their

investigations, while the tabloids just demand more and more, moaning

about soft judges and congratulating only themselves for any courtroom

results they regard as a success. This is an implicitly corrupt

situation but no more, since the judges seem to take this masochistic

stance willingly. Up to the end of the 1980s, when a series of

sensational wrongful convictions could no longer be ignored, it was

combined with a resolute refusal by the courts to find tabloids in

contempt, however outrageous their attempts to influence the outcome of

trials in progress.

With the police, there was an expressly corrupt

relationship well established by the 1970s, that continued into the new

millennium. In story after story, there were aspects that could only

have come from police leaks of confidential information, almost

certainly bought and paid for. No one knows for sure because no one

investigated. Who was going to investigate? But now the spell appears

to be broken, and this corrupt relationship has become one of the arms

of the scandal that has engulfed the press, starting with the News of

the World, and with investigations continuing. But for decades the

tabloids came to regard themselves almost as a branch of the police,

and informally the police concurred, relying on journalists to use

investigatory methods from which they were barred, such as illegal

surveillance and stings.

The early 1980s brought together a set of circumstances in which Rupert

Murdoch was able to lead his press organisation into an implicitly and

perhaps expressly corrupt relationship with government itself. His two

titles were now long-established market leaders, with far away the

largest weekday and Sunday sales respectively (at that time around 3.5

million for the Sun and 4 million for the News of the World), and he

had made enough money from these to be ready for some major

acquisitions. He and the new Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher

evidently got on well and certainly saw eye-to-eye politically. Both

thought of themselves as libertarians, but both actually had a strongly

authoritarian streak when it came to certain kinds of 'law and order'.

Moreover Thatcher thought of herself as a political crusader, with a

crusader's disregard for the ethics of methods in pursuit of what they

regard as a good cause.

So it was that Thatcher's government used discretionary aspects of

competition law to nod through Murdoch's 1981 purchase of the Times and

Sunday Times while blocking all the other bidders. It was completely

blatant, but that was Thatcher's style. Since then, the courts have

developed some powers to oversee this kind of government misuse of

discretion, but then, even if they had regarded themselves as able to

intervene, they would probably have refused -- taking the line of the

judges who in the 1985 Ponting case stated that the 'public interest'

meant, in law, the interests of the government of the day, no more, no

less. The purchase gave Murdoch's empire a wholly new cachet of

respectability, and his ability to cross-subsidise (a regular Murdoch

tactic), together with a certain limited vulgarisation, enabled him to

bring the Times papers into contention for broadsheet (upmarket) press

dominance. Later in Thatcher's term the government did what it could to

smooth the path of Murdoch's nascent satellite TV business, Sky,

culminating in nodding through its 1990 merger with its main competitor

to produce an effective monopoly, BSkyB, nominally a merger of equals

but in practice a Murdoch takeover.

In return, Murdoch made sure his tabloids gave unstinting support not

only to Thatcher's party, the Tories, but to her wing of it, what we

would now call neocons. Is it corrupt for a proprietor to direct his

paper's allegiances in this way? As time was to show, it certainly had

a corrupting effect.

In 1990 the Tories deposed Thatcher as leader and Prime Minister,

replacing her with John Major. The main policy difference between them

was on British integration into the European Union: Thatcher and

Murdoch wanted less, seeing Europe as a source of bureaucracy and

liberal social policy; Major and most Tory MPs wanted more, seeing

integration as good for business. However, when it came to the 1992

election, with a choice between Major and an outright socialist,

Labour's Neil Kinnock, Murdoch backed Major. After the election, in one

of its most remembered headlines, the Sun claimed responsibility for

Major's narrow victory. Whether it really was "the Sun wot won it" for

Major is still debated, but what is clear is that, as the biggest

selling and most aggressive paper, it was able to run a very effective

campaign to make Kinnock a figure of ridicule, whereas Major, himself

no slouch when it came to ridiculous ideas and tactics, got away with

it. He may have wished he hadn't, because less than six months after

the election his economic policy of European Monetary Union blew up in

his face on 'Black Wednesday', after which he in turn become a national

joke.

The Labour Party had expected to win in 1992, and the loss caused it to

have an existential crisis of confidence, believing that if it could

not win in the conditions of 1992, it could never win again.

Collectively it decided to abandon all of its former policies and

principles and instead concentrate only on making itself 'electable',

meaning in practice acceptable to the tabloid press and especially to

Murdoch. In 1994 the Party chose a messianic new leader to carry this

transformation through, Tony Blair, a worst-of-all-worlds combination

of neocon and politically correct, who immediately began to cultivate

Murdoch. Ironically, by this time no transformation seemed necessary,

as the Tories were completely discredited by Black Wednesday, and

Labour riding high in the polls. Perhaps they feared that even from a

much stronger position than in 1992, the Sun could still snatch victory

from their grasp. Or perhaps they saw the chance of a victory of

epoch-making scale and thought it worth betraying every principle for

that, too. At any rate, the transformation into New Labour, once

underway, was unstoppable. And an essential aspect of New Labour was

its corrupt partnership with Murdoch.

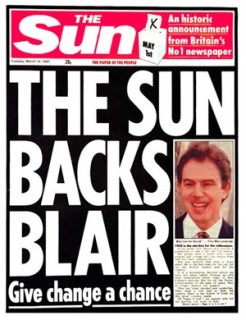

The

transformation paid off, Murdoch switched all his papers to support

Labour in time for the 1997 election, and New Labour won an

obliterative majority of seats (though with only a small plurality of

votes). New Labour, in power, assessed all policy and legislation

primarily by how it would play in the tabloid press, especially the

Murdoch press, and very much including the News of the World. Murdoch

and his editors were now not just feted in the corridors of power but

actively consulted over policy behind the scenes. They must have felt

like untouchable masters of the universe!

The News of the World's obsession with pedophiles was pandered to

firstly by the creation of the Sex Offenders Register, widely regarded

as a pedophile register, which enables police to keep tabs on anyone

convicted of a wide range of vaguely 'sexual' offences; and secondly by

the creation of Sex Offence Prevention Orders, which enable the courts

to impose arbitrary conditions on those convicted of a somewhat wider

range of 'sexual' offences after they have served their sentences. The

Sexual Offences Act 2003 completely rewrote the law in that area,

generally raising penalties and making offences easier to prove. All

penetrative sexual contact with anyone under 13 was henceforth not to

be distinguished from rape. Penalties were also greatly increased for

'child porn' offences, and this interacted with another of Blair's

populist creations, because the new higher sentences made many 'porn'

offences, including some kinds of possession, eligible for the new

'IPP' (

Imprisonment for Public Protection) indeterminate sentences, effectively life imprisonment. To top it

off, in 2009, New Labour made illegal the possession of "disgusting"

drawings of children.

But one tabloid demand New Labour did not accede to was that for

US-style public access to the Sex Offenders Register. This was because

the police, who would have to clear up the mess, advised against.

In

2000, a new editor at the News of the World, Rebekah Wade (since

renamed Brooks after a remarriage), decided to make her mark by

latching on to a recent murder of a child

2,

assumed to have been by a pedophile, in order to campaign for such

access. A main feature of the campaign was that every week the News of

the World would itself publish the names, photographs and approximate

addresses of 50 'convicted pedophiles'.

In the event, the campaign lasted two weeks before the paper gave in to

government and police demands to end it, amid a welter of vigilante

attacks and riots. Partly thanks to the low quality of the photos and

imprecision of the addresses, partly to the usual carelessness of

vigilante mobs, most of the attacks were against people who were not

even those the paper named but had similar names or looked a bit like

them.

In one notorious incident a pediatrician was driven from her home

because pediatrician sounds a bit like pedophile. In the following

weeks there were calls by some MPs for Wade to be prosecuted for

incitement. Instead, New Labour gave her the concession of granting

certain members of the public controlled access to the Register in

certain limited circumstances, so she could claim some kind of victory.

Hauled before the Leveson Enquiry in 2011, she was still citing this

campaign as her prime example of the good that she and the News of the

World had done.

To Wade's time as editor date the earliest and some of the worst

examples of voicemail hacking to figure in the current investigations,

including that of Milly Dowler

3.

The above should make clear that this kind of technique was business as

usual for the News of the World, typical of their 'undercover' methods

over many decades, but perhaps in 2000 there was an especially

poisonous mix of complacency, self-righteousness and arrogance, spawned

by the nature of the partnership with New Labour. On the one hand, they

thought they were untouchable, and rightly so then and for several

years after; on the other hand, for reasons explored above, they felt

that any and every investigative technique was justifiable when used by

them.

One thing that had changed, gradually, since the 1970s, was the

continued rise of celebrity culture. News of the World took part in

this, turning its usual dark arts towards uncovering confidential facts

about celebrities and turning them into front-page gossip. All the

papers did it, but the News of the World was able to use its

established techniques to go further, and darker.

In 2005, things began to unravel just a little. That well-known

celebrity, Prince William worked out that two stories about him in the

News of the World could only have come from someone listening to his

voicemails. The police were called in and their investigation led to

the prosecution of the paper's Royal Editor, Clive Goodman and a

private investigator employed by him, Glenn Mulcaire. Both pleaded

guilty to phone hacking and received short jail terms (4 and 6 months).

The editor, Andy Coulson, resigned but pleaded ignorance on his own

part.

In the months and years that followed a growing number of celebrities

also identified stories that must have arisen from the same method. The

paper faced a burgeoning number of civil lawsuits and set aside

millions of pounds to settle them. The police however refused to

investigate any further. There is some disagreement and mystery over

the reason why. They claimed they had legal advice that gave such a

narrow definition of hacking that investigations would not be worth the

trouble, but the lawyer who was supposed to have given this advice

later denied it. The News of the World began settling civil cases

without admitting liability, and peddled the public line that one

'rogue reporter' had been responsible for a small amount of hacking.

In

their favour was the fact that the Tories now appeared to be following

the trail that New Labour had blazed. They had expected their defeat in

1997, but when they failed to make any recovery in 2001, and only a

weak recovery in 2005, they too had a crisis of confidence, and decided

they must compete with New Labour in courting the Murdoch press. Their

new leader, David Cameron, employed the same Andy Coulson who had

resigned as News of the World editor over hacking, as his

director of communications. The message to Murdoch was that even with a

change of government, his empire's cosy position of influence would be

maintained.

Blair was succeeded in 2007 by the much less neocon Gordon Brown, who

was not content with Blair's fawning relationship with the tabloids,

just as Murdoch switched sides to Cameron's now more obliging Tories.

Brown soon became deeply unpopular, though whether this was more to do

with the Murdoch papers or more with his own character flaws is

debatable. At any rate, he deeply resented Murdoch's change of side,

and the government protection enjoyed by the News of the World seems to

have been lowered.

In these circumstances, one of Murdoch's competitor papers, the liberal

Guardian, began to look behind the News of the World's unconvincing

denials of systematic phone hacking, and itself began to receive leaks

from the police that helped with this. In 2009, the Guardian named a

new tranche of people whose phones had been hacked, including senior

politicians. These names came from Mulcaire's notes, seized by police

in 2005, but the police had done nothing about them, not even informing

the people who had been hacked. This led to a further spate of lawsuits

against the News of the World, and in the course of one of these it

emerged that Mulcaire had been commissioned not only by Goodman, but

also by Ian Edmondson, a senior editor. With that, the paper's "one

rogue reporter" defence fell apart. It now desperately tried to

pre-empt events by switching into 'full co-operation' mode and

volunteering a new tranche of evidence to the police, who began a new

investigation into hacking, Operation Weeting.

In 2010 a new Murdoch-friendly Tory government took power, with

however, the spectre of a Murdoch-hostile Liberal Democrat party as

coalition partners. Murdoch now launched a bid for the BSkyB

cable/satellite TV shares he did not already own. He already had

effective control but wanted to make this unchallengeable and secure a

bigger share of profits. He expected once again that the government

would use its discretion to wave him through the monopolies procedures

in what many assumed was a crude quid-pro-quo for supporting Cameron in

the election.

But the phone hacking affair was not going away and with a gradual drip

of revelations related to it and Operation Weeting, the government's

closeness to Murdoch steadily became more and more of an embarrassment.

In January 2011, Coulson resigned as Cameron's communications director,

blaming the publicity, though still claiming innocence himself.

On 4 July 2011, citing a mysterious police contact, the Guardian

reported that in 2002 the News of the World had hacked the voicemail of

Milly Dowler, a schoolgirl who at that time had been missing for a week

and who it later turned had been murdered. More than that, the

Guardian's source claimed, when the News of the World realised that her

voicemail box was full, they deleted some of the messages, to make room

for more that they could listen to and report on. This caused her

mother to believe that Milly herself had deleted the messages and was

therefore still alive, a belief which the News of the World duly and,

said the Guardian, hypocritically, reported. Checking further the

content of the News of the World, the Guardian noted that the paper had

hardly even bothered to cover up its hacking, directly reporting on

particular messages that had been left for Milly, and saying that they

had been left for her in her voicemail.

Hacking the voicemail of celebrities and royalty was one thing; a

murdered schoolgirl was another. Suddenly the News of the World's

sleaze came back to bite it with a vengeance and it was itself the

target of a massive and irresistible scandal. With its major

advertisers announcing boycotts, and a boycott by readers likely, the

paper closed down, publishing a final 'souvenir' edition that very

weekend, July 10.

Later it turned out that those messages had probably not been deleted

by the News of the World but by an automatic system that cleared them

after a certain time. But that was a detail. The fact of the hacking

was beyond doubt. As investigations continued, it became clear that

News of the World reporters had hacked the voicemails of the parents of

other child murder victims too.

A further consequence was that Murdoch's share purchase at BSkyB fell

through. Cameron gave the task of assessing it to a known friend and

supporter of Murdoch, Jeremy Hunt. But the very fact that Hunt was

known to be so close to Murdoch was going to make it politically too

embarrassing to nod through the deal, and July 13 Murdoch abandoned it.

Since then, information turned up by Operation Weeting has led to two

additional police investigations into News of the World and other

papers: Operation Elveden into corrupt payments to police and other

public officials and Operation Tuleta into computer hacking. These are

still underway – reportedly Tuleta is no more than a scoping exercise

prior to a full investigation. So far there have been arrests of

journalists from the Sun and the Times as well as the News of the

World. Trials have begun of a number of people including former News of

the World editors Rebekah Wade/Brooks and Andy Coulson, though these

are still at an early stage.

Is it too much to hope that Murdoch himself might live to face trial?

He was very much responsible for the standards and methods of his

papers. Although voicemail hacking was probably fairly new in 2002,

because voicemail itself was fairly new, it was typical of the methods

Murdoch always encouraged his papers to use, the more so in the

atmosphere of corrupt political hobnobbing and untouchability that his

empire always sought and benefited from. Since his first acquisition of

the News of the World, he has been known among journalists as the Dirty

Digger, and the nickname is apt.

Perhaps a greater threat to Murdoch's empire is a prosecution in the

United States, e.g. under the Corrupt Foreign Practices Act, as the

courts there are less likely to pull their punches. He could follow in

the illustrious footsteps of another former UK press baron jailed in

the USA, Conrad Black. However, as owner of Fox TV, the Murdoch empire

has become extremely influential in the USA, too. I cannot say whether

it has similar kinds of corrupt immunity, but I would not be surprised.

Still, there is at least the possibility of the entire monstrous

edifice of News Corporation being brought down and Murdoch seeing the

inside of a cell.

So – ding, dong! -- the News of the World is dead at long, long last.

Sadly the attitudes and laws it did so much to foster live on.